‘They are living separate lives’

Patrick Bradley (Photo by Lily Mott)

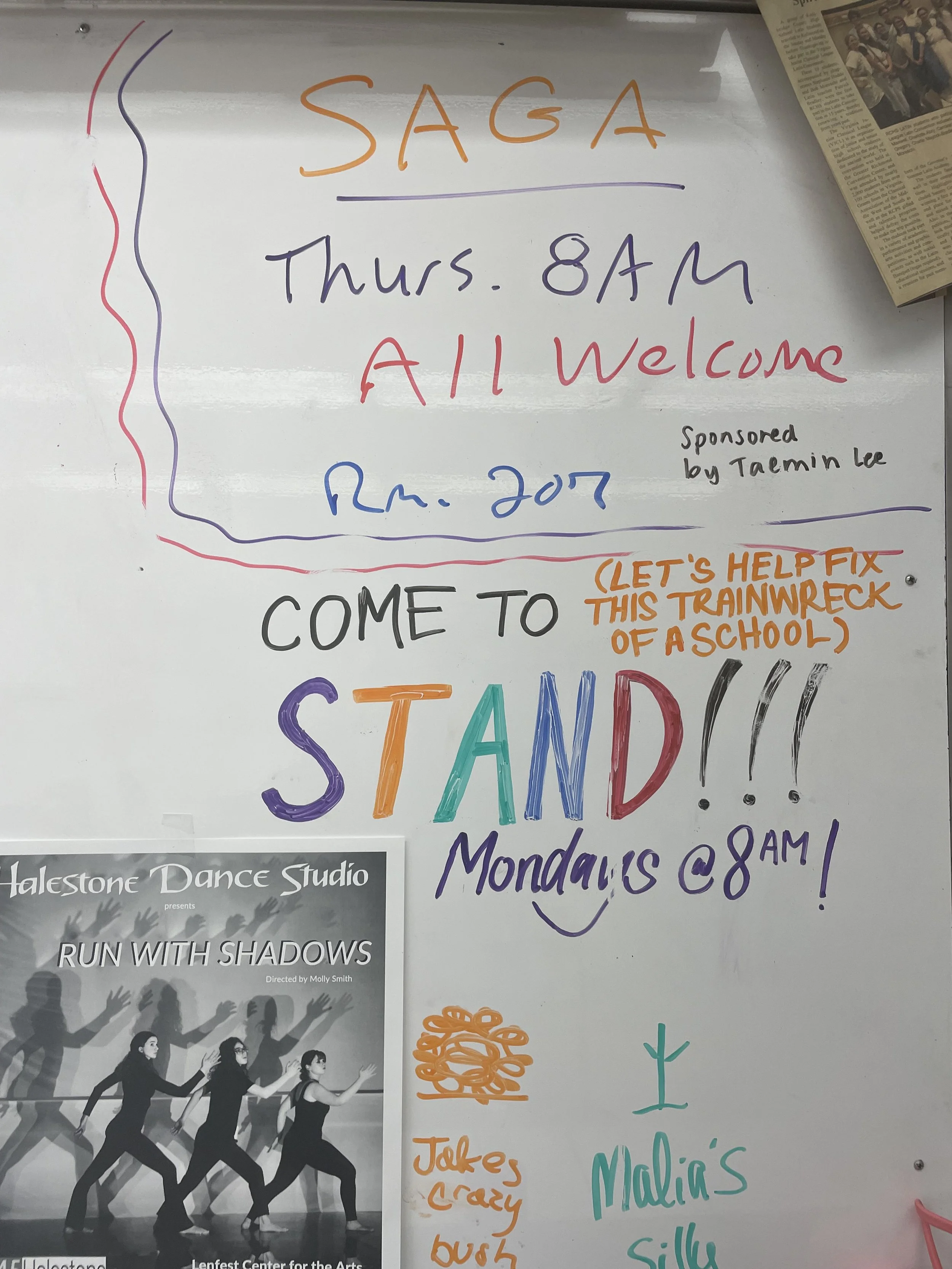

Bradley serves as the faculty sponsor for two student groups: the Sexuality and Gender Awareness (SAGA) and the Student Association for Non-Discrimination (STAND) clubs. He decorates his classroom with LGBTQ+ pride flags, Black Lives Matter stickers, and “safe space” signage.

Morgan McCown (Photo by Lily Mott)

“I was a county student, and I felt the difference between the kids that went to Lexington public schools,” she said. “The county kids are typically what are known as the rednecks.”

She ran for Rockbridge County School Board in 2021 on a campaign of transparency, parents’ rights, and opposition to critical race theory. But she lost.

McCown says that part of the divide between city and county students is based on their career goals. Many county students participate in the career and technical education programs at the high school. She says county students who are learning a trade sometimes feel like they’re not taken as seriously as city students who are college-bound.

“For a long time, kids that were going to community college, or going after a trade, you never saw them posted on Facebook,” she said. “But you saw the college signings.”

Mike Craft, the high school’s principal, said there is no county-city divide. “It's not us versus them,” he said. “We're working together to do what's best for our children.”

Cora Conway, a ninth-grader at Rockbridge High, says she noticed that her classmates coming from the city’s Lylburn Downing Middle School tend to enroll in honors classes, and students from the county’s Maury River Middle School do not.

Natasha Gengler, a math teacher at the high school, says the academic differences between students from Rockbridge County and Lexington are real. But she also says the difference between the parents is a concern.

“Parents of the Lexington students are so involved in their education and talk to me and reach out a lot,” she said. She says she often hears little from parents in the county, even when she tells them that their child is failing.

Patrick Bradley, who’s taught Latin at Rockbridge County High School for more than 20 years, says city and county students seem to occupy different spaces. “Now how much has that changed over the years? I have a feeling it hasn't changed too much, that they are living separate lives.”

In his first year as a teacher at the high school, Bradley remembers asking a student about whether city and county students got along.

The student, who was from the county, described city kids as “a bunch of stuck-up, preppy elitists.”

Signs on Bradley’s door (Photo by Bri Hatch)

Like Bradley, Rockbridge County resident Morgan McCown said she sees “a huge public perception difference” between city and county students.

McCown graduated from Rockbridge County High in 2008, taught financial literacy at the high school for two years, and now has two children in the county school system.

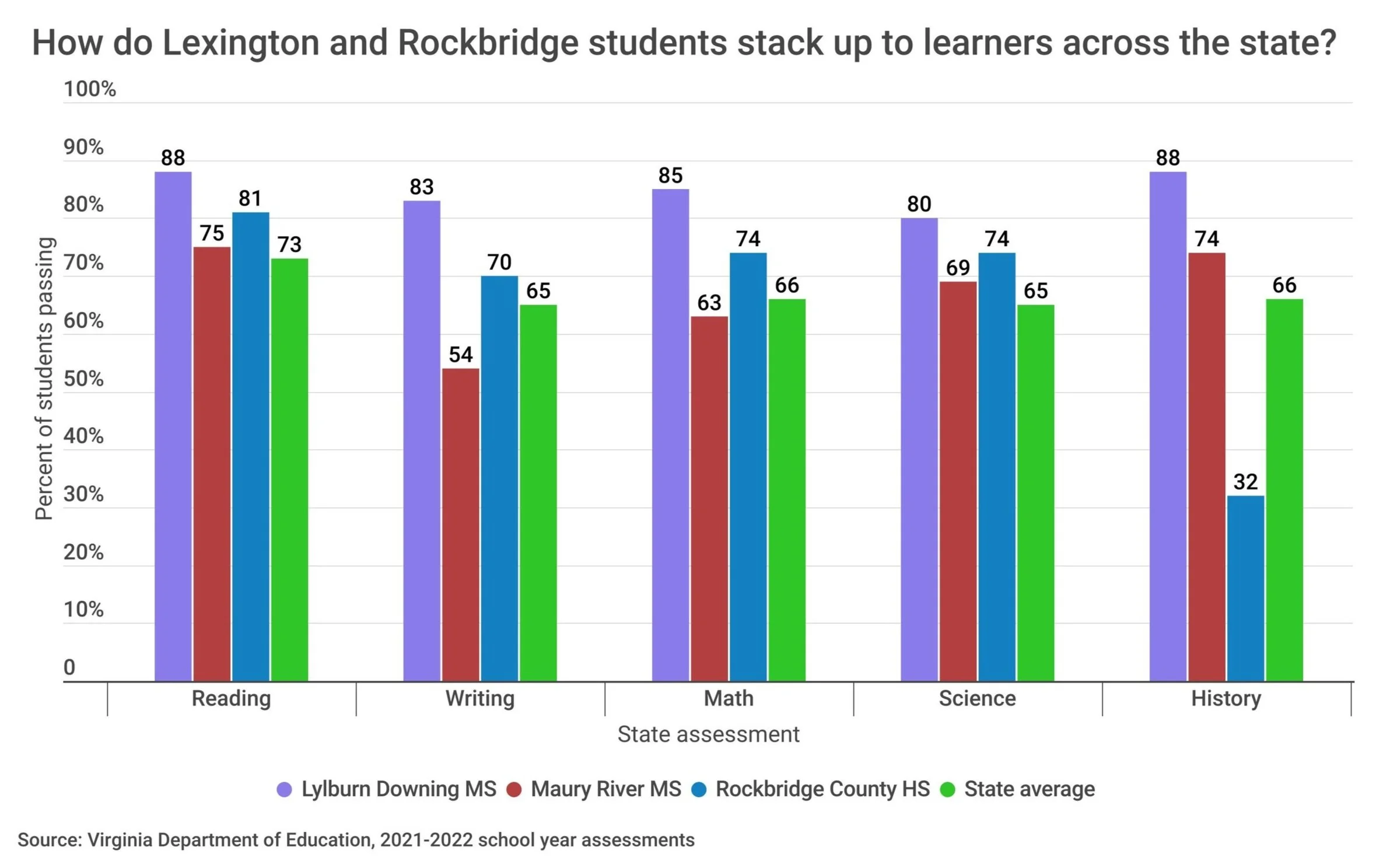

Lexington City Schools ranked second out of 132 public school divisions in Virginia for performance on the 2021-2022 standardized tests.

Specifically, eighth-graders at Lexington’s Lylburn Downing Middle School performed higher on every state assessment than eighth-graders at Maury River Middle School in Rockbridge County in the 2021-2022 tests.

Rockbridge County Public Schools ranked 78th out of 132 public school divisions based on the same 2021-2022 standardized tests.

Conway says county students look at the Lylburn Downing students as “rich, private school kids, which we aren’t really. They kind of hold us against that.”

‘Learning there is better’

But some county parents recognize the disparities in learning between the city and county schools. So they pay $1,500 per year to send their children to Lexington’s K-8 schools.

In the 2022-2023 school year, 148 non-resident students attended Lexington City Schools. Most of them live in Rockbridge County, but some live in other neighboring counties. Non-resident students account for about 30% of the total students enrolled in city schools.

Elizabeth Smiley (Photo by Lily Mott)

Elizabeth Smiley, a Rockbridge County resident, says she is considering sending her 7-year-old son to the city’s Waddell Elementary instead of the county’s Central Elementary. She says she feels the county school does not properly communicate with her.

In early May, her son “ran into a metal pole” at recess, Smiley said. “And they never sent him to the nurse, never called me. Nothing.”

Smiley, who works as a custodian in the Phi Zeta Delta fraternity house at Washington and Lee University, says she believes city schools have more resources.

“County kids don’t get the one-on-one time,” she said. “The county has a lot more kids. I feel like their classrooms are a lot bigger.”

She says she wants her son in smaller classes. “He’d probably get better attention than he gets now,” she said.

Smiley says she thinks Lexington schools are expensive. But she says she feels like she has no choice.

Dan Lyons, who served as Lexington City Schools’ superintendent from 2002 to 2015, says county parents used to line up outside his office every year at midnight on the first day of kindergarten registration to apply to get their children into Lexington schools.

“When I'd come in at like seven in the morning, they'd be lined out the door to wait,” said Lyons, who is a member of the Rockbridge County Board of Supervisors. “But once you were in it, like if you got in kindergarten, you were good until you finished eighth grade.”

Rockbridge County students can apply to enroll in the Lexington system at any grade level, Lyons said. But most parents try to get their children in when they start kindergarten and keep them in the city schools until they finish eighth grade.

“I guess the learning there is better,” Smiley said, referring to the Lexington schools, “because it's smaller, and you don't have 15 kids against one teacher.”